Who do you think you are? What makes you think you can call yourself a writer? You know they were just being polite when they claimed they liked your writing. It’s only a matter of time before everyone realises you have no talent. Nobody wants to read what you write. You’ve got nothing original or interesting to say.

Who do you think you are? What makes you think you can call yourself a writer? You know they were just being polite when they claimed they liked your writing. It’s only a matter of time before everyone realises you have no talent. Nobody wants to read what you write. You’ve got nothing original or interesting to say.

Let me be clear: I am not saying these horrible things to you, and I never would. But I bet you’ve said something like this to yourself at some point. I know I have.

It would be a rare writer indeed who did not wrestle with some level of self-doubt. For some, however, those uneasy feelings go deeper, leading us to believe that we are genuinely unworthy of our efforts and achievements. If heeded, such feelings can fool us into thinking we are nothing more than fakes, frauds, phonies—not ‘real’ writers at all.

Impostors, in fact.

Known by various names, the impostor complex is a treacherous tangle of thoughts that seek to convince you any success you experience is due to luck or chance or circumstance—or maybe it was the weather? Whatever the case, it was not the result of any effort, skill, or ability on your part. And by the way, you know you’re never going fluke a win like that again, right?

The impostor complex exhorts you to believe that any minute now—indeed, any second—you will be exposed as the incapable, inadequate, talentless charlatan you feel yourself to be. And it keeps viciously insisting, against all evidence, that you’re not ready, you’re not good enough, you don’t deserve it, you shouldn’t, you mustn’t, you can’t.

Honestly? It’s exhausting just writing about it, let alone having those ideas gnawing remorselessly at you.

If such erroneous notions are eroding your confidence, here are a few things to keep in mind.

1. According to Tanya Geisler, an expert in this area, the impostor complex affects high functioning, high achieving people who hold strong values of integrity, mastery, and excellence. That’s you, incidentally, even if you don’t recognise yourself in that description. (You see how this works?)

2. The impostor complex only shows up when something really matters to you. It diminishes your existing accomplishments and makes shaky every potential new venture. If you feel it in relation to your writing, take it as a sign of how important your words and your role as a writer are to you.

3. Three effects of the impostor complex are to make you doubt your capacity, to prevent you from acting, and to keep you isolated. Clearly, none of that is fun, and nor is it particularly conducive to writing.

4. Appearances to the contrary, it’s highly likely that everyone you have ever respected, most of the people you have met, and all those you wish you could be more like feel this way too. Yes. All of them. You are in good company.

5. While it is unlikely that the impostor complex can ever be completely defeated, there are ways to curtail its effects. I strongly recommend that you start identifying and practising these.

Some suggestions for overcoming the impostor complex include:

- recognising it for what it is: a malicious mess of conjecture that is as unhelpful as it is untrue

- understanding that your doubts are not proof of your inability but rather an indication of your desire to meet your own (almost certainly unfeasibly) high standards of integrity, excellence, and mastery

- questioning the accuracy of the messages you receive about yourself, your work, and your worth, whether these arise internally or come from external sources

- giving yourself generous evidence of your abilities, resources, achievements, and brilliance, because you have an abundance of these, even if you don’t always acknowledge them

- making meaningful and supportive connections, and—here’s the tricky bit—actually believing these people when they encourage and praise you

- developing the capacity to encourage and praise yourself; after all, if your mind can persuade you to think you’re an impostor, it can also point out that you’re not.

There are lots of other strategies you might try, but my advice to help you face the impostor complex is to just keep writing.

Keep making, keep doing, keep creating, despite what those vicious whispers tell you. Use your voice and cultivate the courage to trust that your work matters—that YOU matter—because it’s true.

Truer than any impostor could be.

How has the impostor complex affected your writing? What strategies do you use to subdue it? Are there any resources or tools on this topic that you can recommend to others?

Note: Much of the information for this article came from the work of Tanya Geisler. If you’d like to know more, please visit her online. And for those pondering the correct spelling of impostor/imposter, have a read of this.

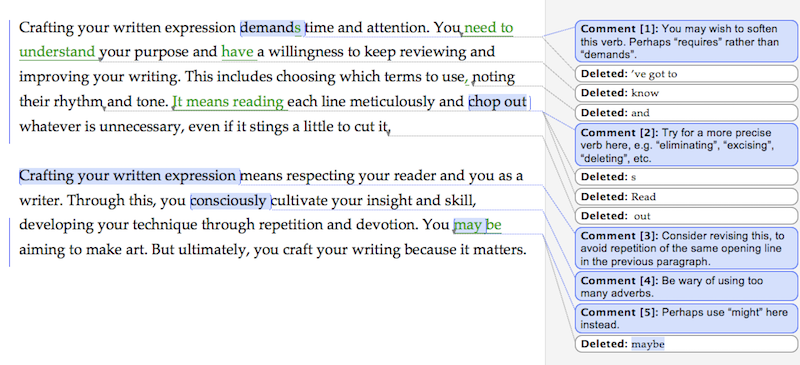

Try as we might to avoid it, editing can sometimes be distressing. After putting their hearts into their craft, writers can feel slighted and even assaulted by the comments, questions, corrections, and suggestions that editors strew through their manuscripts. Although it is never an editor’s intention to cause anguish, the distress that writers might feel at having their words so closely scrutinised is real.

Try as we might to avoid it, editing can sometimes be distressing. After putting their hearts into their craft, writers can feel slighted and even assaulted by the comments, questions, corrections, and suggestions that editors strew through their manuscripts. Although it is never an editor’s intention to cause anguish, the distress that writers might feel at having their words so closely scrutinised is real. If you have ever wondered about when it’s right to say “may” and when to use “might”, you may find this article interesting. Then again, you might not. Either way, let’s investigate.

If you have ever wondered about when it’s right to say “may” and when to use “might”, you may find this article interesting. Then again, you might not. Either way, let’s investigate. There are moments in life that echo with unexpected resonance. They arise like reminders of a truth held deep in your being that you may not recognise or express until it is brought to light by an external catalyst. Such moments occur for me when I’m wandering through an art gallery and find myself drawn to certain works that rouse a powerful response. They happen, too, when I’m reading and I encounter an image or phrase that renders the world more lucid or beautiful. Then there are the times when a comment from an admired author illuminates an intrinsic understanding.

There are moments in life that echo with unexpected resonance. They arise like reminders of a truth held deep in your being that you may not recognise or express until it is brought to light by an external catalyst. Such moments occur for me when I’m wandering through an art gallery and find myself drawn to certain works that rouse a powerful response. They happen, too, when I’m reading and I encounter an image or phrase that renders the world more lucid or beautiful. Then there are the times when a comment from an admired author illuminates an intrinsic understanding.