Editors are curious individuals—almost as quirky as authors. While there are certain principles of clear communication and grammatical accuracy to which most editors will adhere, each of us has our own idiosyncrasies and inclinations. When it works, the relationship between a writer and an editor can be enjoyable, enlightening and inspiring for both people. But how can you tell if it’s going to be like this?

Editors are curious individuals—almost as quirky as authors. While there are certain principles of clear communication and grammatical accuracy to which most editors will adhere, each of us has our own idiosyncrasies and inclinations. When it works, the relationship between a writer and an editor can be enjoyable, enlightening and inspiring for both people. But how can you tell if it’s going to be like this?

One way I try to address this question is by providing my potential clients with a sample edit.

Here’s how it works. When you contact me, I get an initial sense of whether or not I am the right editor for you. If I think we may work well together, I will ask you to send me your manuscript, assuring you that I’ll keep it safe and confidential while it is in my care. I then edit part of the text, generally beginning at the beginning. I use track changes in Microsoft Word when editing. This allows you to see the changes I make, and it enables me to include comments, questions, observations and suggestions within the document.

The image below shows an example of an original draft, adapted from an article previously published on this website.

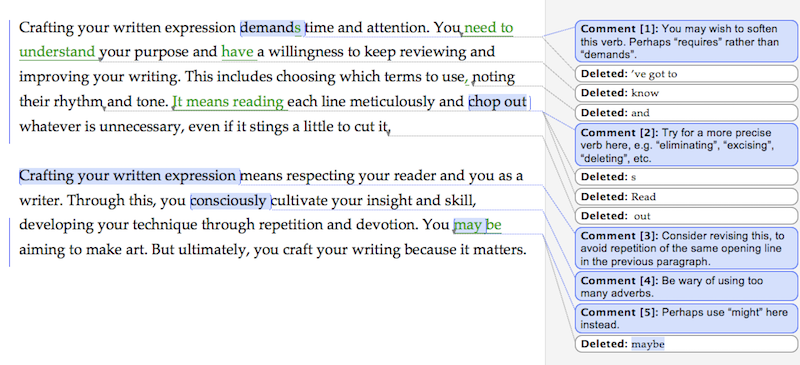

And this is what the text looks like when it is marked up using track changes.

As you can see, I have made a few corrections (shown in the text in green), along with some suggestions (in the blue comment boxes on the right-hand side).

Taking these corrections and suggestions into consideration, here’s how the revised version might read.

Of course, if you had written these paragraphs and had received this sample edit from me, you might have made different decisions about their final form. That’s the delightful thing about writing and editing: they are both expressions of unique creativity and are both so open to interpretation and invention.

By providing you with a sample edit, I give you the opportunity to see if your creativity and mine align. When they do, we each have the chance to engage in an artful and enjoyable experience of editing.

Have you ever received a sample edit from an editor? Did that influence your decision to work with that person? What insights or information do you want to have before you choose who will edit your writing?

Photo by Joanna Kosinska on Unsplash

Try as we might to avoid it, editing can sometimes be distressing. After putting their hearts into their craft, writers can feel slighted and even assaulted by the comments, questions, corrections, and suggestions that editors strew through their manuscripts. Although it is never an editor’s intention to cause anguish, the distress that writers might feel at having their words so closely scrutinised is real.

Try as we might to avoid it, editing can sometimes be distressing. After putting their hearts into their craft, writers can feel slighted and even assaulted by the comments, questions, corrections, and suggestions that editors strew through their manuscripts. Although it is never an editor’s intention to cause anguish, the distress that writers might feel at having their words so closely scrutinised is real. I have such admiration for artists. Painters, illustrators, photographers, sculptors, musicians, designers, dancers, and more: they all reflect and refract the world through their work, providing us with insight, delight and occasionally a new perspective on life.

I have such admiration for artists. Painters, illustrators, photographers, sculptors, musicians, designers, dancers, and more: they all reflect and refract the world through their work, providing us with insight, delight and occasionally a new perspective on life. I could make this an incredibly short article by just writing the word ‘No’, but of course there’s more to the story than that. In this case, there is also a story behind the story. It explains why this issue is currently on my mind.

I could make this an incredibly short article by just writing the word ‘No’, but of course there’s more to the story than that. In this case, there is also a story behind the story. It explains why this issue is currently on my mind.