One of my lovely clients contacted me recently regarding his current manuscript. He ended his email with the words: “I am trying to encourage myself to keep going.”

One of my lovely clients contacted me recently regarding his current manuscript. He ended his email with the words: “I am trying to encourage myself to keep going.”

If you are a writer, then you know—with a weighty, world-weary certainty—that writing is not always fun. It is rarely easy and often unrewarding. Finding the motivation to keep putting one word after another (while most likely also going back to delete, tweak or shuffle a whole bunch more) is a challenge when you lack inspiration. Even the most eloquent and impassioned writers get disheartened from time to time.

The hard truth about encouraging yourself to keep writing is that it’s entirely up to you.

Leaving aside the commonly quoted notion that we write because we ‘must’—as if impelled by an inner imperative that seeks to be appeased—the reality in most cases is that we write because we choose to do so. I’m sorry to say it, but with some exceptions, it makes no essential difference whether we write or not.

But.

This does not mean your writing is not important.

It is, and that’s the point.

What you write does not have to change the world. It doesn’t need a million and six readers, but it does have to mean enough to you that you will find some way to keep going with it, even when motivation and inspiration are low. Even when you doubt yourself and your ability. Even when you are utterly discouraged.

The only person who can incite you to continue is you.

That is what will stop you from giving up.

Maybe you hope your story will help others. Maybe you yearn to educate or entertain, or perhaps you are, quite simply, a kinder person when you give yourself time to write. Whatever your reasons are, remember them and repeat them to yourself in moments of misgiving.

If you’ve lost enthusiasm for your writing, try taking a new approach to it. Pick a different time or place to write. Set yourself challenges or restrictions and work within them. If you currently spend hours groaning over your computer screen, limit yourself to handwriting for no longer than thirty minutes a day. If you’re stuck on a particular passage or chapter, prohibit yourself from working on it for a week.

It is also wise to find external support, whether it is from a family member, a friend, a fellow writer, an imaginary mentor or even an editor. Although you are the only one who can decide whether or not to persist with your writing, you do not need to feel alone during difficult times. Meaningful affirmation can come from others, especially if they see the value that writing has for you.

Sometimes the inspiration comes later and sometimes it doesn’t come at all. The trick is to keep going regardless.

If you are really struggling and none of these suggestions brings you any relief, then it may be time to let it go. Despite its myriad frustrations, writing is ideally an enriching activity. If it has ceased to be so for you, perhaps the most generous choice you can make is to do something else instead. The world is full of wonders that have nothing to do with words (or so I’m told). You could always go and discover some.

As writers, we must come with ideas, dedicate the time to write, linger and labour over language, redraft and revise, endure—or hopefully enjoy—being edited, anticipate rejection, withstand doubts, and keep writing despite everything. In addition to this, we are responsible for generating and sustaining our own encouragement.

That might seem unfair. It may even be enough to make you want to give up. But you are the one who gets to choose.

So tell me: what are you going to do?

What discourages you about your writing? What do you do to motivate and inspire yourself? What support or advice can you share with others who feel like giving up?

I could make this an incredibly short article by just writing the word ‘No’, but of course there’s more to the story than that. In this case, there is also a story behind the story. It explains why this issue is currently on my mind.

I could make this an incredibly short article by just writing the word ‘No’, but of course there’s more to the story than that. In this case, there is also a story behind the story. It explains why this issue is currently on my mind. Among the words that befuddle writers are “that”, “which” and “who”. Although they may seem like simple enough terms, each serves a variety of grammatical functions, depending on its role and position in any given sentence. As some of the functions these three words fulfill are similar, confusion over their usage can arise.

Among the words that befuddle writers are “that”, “which” and “who”. Although they may seem like simple enough terms, each serves a variety of grammatical functions, depending on its role and position in any given sentence. As some of the functions these three words fulfill are similar, confusion over their usage can arise.

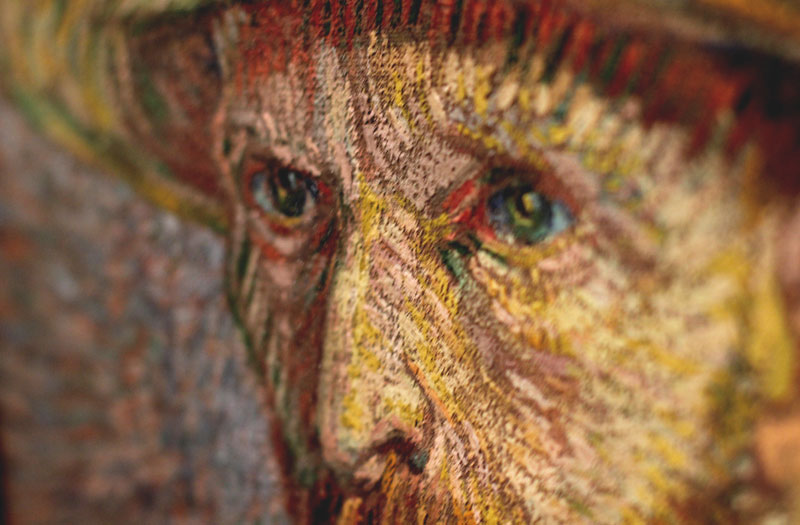

As far as I’m aware, Vincent van Gogh never shared any explicit advice about writing. (If he did and you know of it, I’d be delighted to

As far as I’m aware, Vincent van Gogh never shared any explicit advice about writing. (If he did and you know of it, I’d be delighted to